How your toothbrush became a part of the plastic crisis

Toothbrush design hasn’t changed much since its dawn of time. National Geographic does a deep dive into its history.

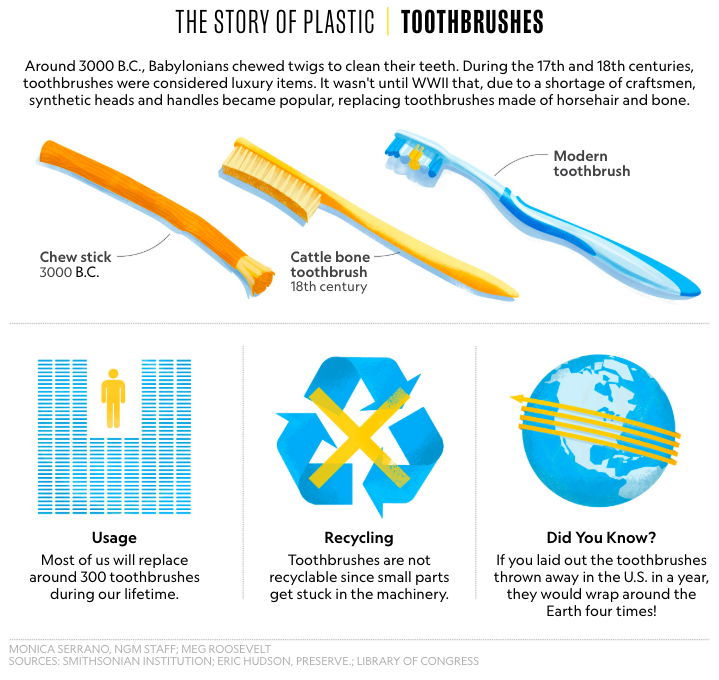

Toothbrush design is little changed from its earliest form. The biggest difference is in the materials: toothbrushes are now all made of at least some plastic. Take a tour of the humble toothbrush and find out how it affects the environment.

At first, years ago, it was just an occasional piece of plastic trash that Kahi Pacarro, the founder of Sustainable Coastlines Hawaii, picked up on the beach cleanups he organized around the state. A straw here, a takeout container there. But one day Pacarro spotted something particularly surprising in the beach detritus: a toothbrush.

Now, in any given Hawaii beach cleanup, he says, it’s not uncommon to pick up 20 or even 100 toothbrushes.

The reason is simple. The total number of plastic toothbrushes being produced, used, and thrown away each year has grown steadily since the first one was made in the 1930s.

“I like to ask people, what’s the first thing you touch in the morning? It’s probably your toothbrush,” says Pacarro. “Do you want the first thing you touch every day to be plastic?”

For centuries, the basic toothbrush was made from natural materials. But during the early 20th century, the giddy early days of plastic innovation, manufacturers started substituting nylon and other plastics into the design—and never looked back.

Plastic has so fully infiltrated toothbrush design that it’s nearly impossible to clean our teeth without touching a polymer. And because plastic is essentially indestructible, that means nearly every single toothbrush made since the 1930s is still out there in the world somewhere, living on as a piece of trash.

Now, some designers are looking for ways to reimagine this crucial, classic object in a way that puts less stress on the planet. But to find solutions to the toothbrush conundrum, we have to understand how we got here.

The best invention of all time?

It turns out people really love having clean teeth. In MIT’s 2003 Lemelson Innovation Index survey, the toothbrush rated higher than cars, personal computers, or cellphones as the innovation respondents couldn’t live without.

Humans have apparently felt this way for a very long time. Archaeologists have found “tooth sticks” in Egyptian tombs. The Buddha chewed sticks into fluffy-ended scrubbers to clean his teeth. The Roman author Pliny the Elder noted that “it makes teeth firm to pick them with a porcupine quill,” and the Roman poet Ovid proclaimed that it was a good idea to wash the teeth each morning.

Tooth care even occupied the mind of the reigning Chinese emperor Hongzhi in the late 1400s, who designed something that looked a lot like the brush we know today. It featured a short, dense pack of boar bristles, shaved off the neck of a hog, set into a bone or wood handle.

That simple design endured, essentially unchanged, for centuries—but not for everyone. Boar bristles and bone handles were fancy, expensive materials, meaning that only the wealthy could afford brushes. Everyone else had to make do with chew sticks, scraps of cloth, their fingers, or nothing at all. As late as the early 1920s, only an estimated one in four people in the United States owned a toothbrush.

War changes everything

It wasn’t until late in the 19th century that the concept of tooth care for everyone, rich and poor alike, started to trickle into the public consciousness. One of the drivers of that transition was war.

Around the time of the American Civil War in the mid-1800s, guns were loaded one shot at a time, with powder and bullets that had been pre-wrapped in twists of heavy paper. Soldiers needed to tear the twists open with their teeth, but many potential fighters lacked even the six well-anchored opposing teeth to rip the paper apart. This was obviously a problem.

The few dentists serving the Union Army despaired at the state of the teeth around them, but dental care failed to take hold as a priority for the North. The Confederate Army, in contrast, conscripted a cadre of dentists who stressed preventative care; one army dentist pushed the message so successfully that soldiers in his unit shoved their toothbrushes in their buttonholes, readily available at all times.

It took two more major military mobilizations to get toothbrushes into nearly every bathroom. By the advent of World War I, the U.S. military recognized that they had a problem, a variant on the cartridge-ripping issue from the Civil War. The otherwise healthy young men they wanted to recruit into service needed six healthy opposing teeth in order to eat the tough, dry military rations. Young man after young man failed that test.

“It’s a little unbelievable, looking from today’s vantage point,” says Alyssa Picard, a historian and the author of Making the American Mouth. “[The military] had a standard, and it’s pretty basic—have six teeth in your mouth so you can chew—and people are not meeting those standards. People who would otherwise be available for fighting? Off the list.”

By World War II, soldiers were instructed in the care and keeping of teeth; dentists were embedded in battalions and toothbrushes were handed out to troops. And when the fighters came home, they brought their tooth-brushing habits with them.