Reduce, reuse, recycle, rejected: Why Canada’s recycling industry is in crisis mode

One year ago, China implemented an import ban on 24 types of solid waste -impacting recycling programs in Western countries. This informative article from the Globe and Mail discusses the issue of plastics waste, China imports, and how EPR and a circular economy can drive change.

Full Story

For decades, Canadians tossed their recyclables into blue bins and never looked back. But with China cutting its imports of scrap plastic by 96 per cent, Canada’s recycling industry is struggling

Desperation had set in. For more than a year, officials in Calgary’s department of waste and recycling services had been unable to find a buyer for truckloads of used plastic.

Recyclers in Canada had balked. And shipping the unwanted material overseas was no longer an option. By March, the officials appealed to Sims Municipal Recycling in Brooklyn, N.Y. – a last-ditch bid to clear a backlog of hard-to-recycle packaging that had swelled to 1,400 tonnes, the equivalent of seven blue whales, stranded, in this case, in trailers at a local landfill.

China’s crackdown on importing used plastics is creating limits on everyday household recycling a half world away, and highlights North America’s addiction to cheap plastics.But even that Hail Mary pass proved futile. “Frankly, even if they deliver it to me for [free], which is a very expensive route for them, given all the freight costs, we would not take it today,” says Sims General Manager Tom Outerbridge, who’s had to recycle a similar version of this bad news more than a few times over the past while.

The extended holding pattern the scrap was forced to endure is a symptom of a much wider emergency engulfing the global recycling industry. It followed on China’s decision, one year ago, to ban the import of 24 types of recyclable commodities. The hard-line new policy, dubbed National Sword, was a response to environmental and health concerns, and also to the “contaminated” state in which recyclables arrived: often in filthy condition, and with random materials lumped into single bales.

Almost overnight, a thriving global trade in recyclable scrap dried up.

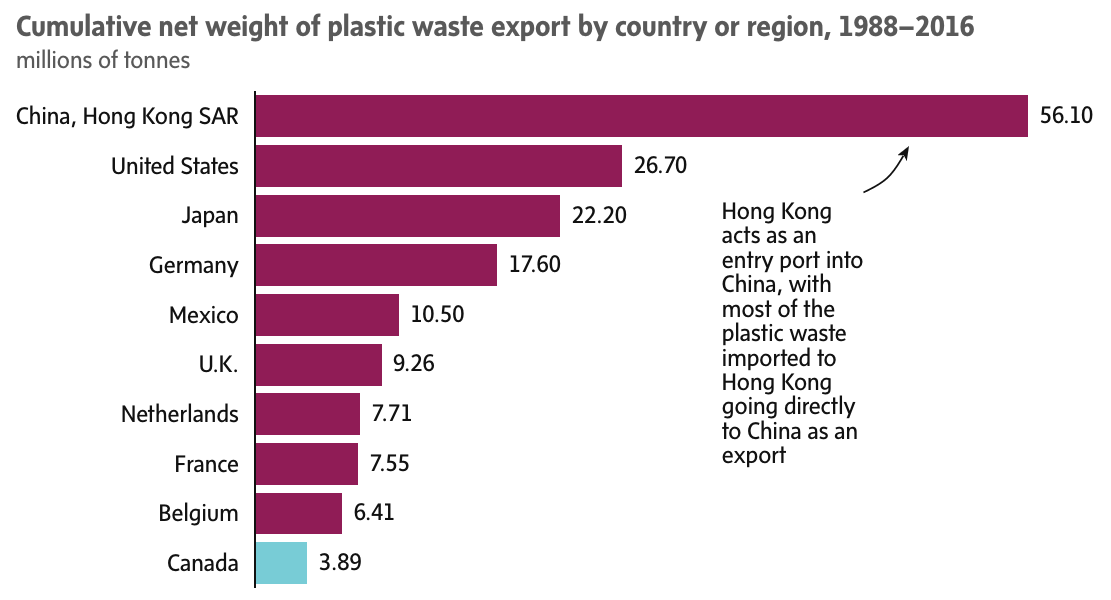

A Globe and Mail analysis of international trade data shows that Canadian exports of scrap plastic dropped by one-fifth last year, with especially steep reductions in the amounts sent to Hong Kong and China – 72 per cent and 96 per cent, respectively. (Chinese imports of Canadian used paper also plunged, by 65 per cent; that drop poses less of a challenge – paper is a homogeneous commodity and generally easier to recycle).

The data analysis, together with dozens of interviews with city officials across Canada, as well as landfill operators, private waste haulers and processors, brokers and others, paints a portrait of an industry in full-scale crisis, stung by rising costs – and inundated by a mountain of trash no one wants to buy, or even, in many cases, take for free.

China’s crackdown, in turn, is creating new limits on everyday household recycling a half a world away, while casting into relief our addiction to cheap plastics and other consumer packaging.

“We are in a crisis,” says Christina Seidel, executive director of the Recycling Council of Alberta, “that could really undermine the success of our industry.”

China’s refusal to continue its role as the world’s biggest recycling bin has pushed up recycling costs by as much as 40 per cent, pulling back the curtain on the shaky economics that underpin curbside recycling.

To cope, cities and companies have been scrambling to upgrade equipment and add labour to sort, handle and prepare paper and plastic cast-offs. There is also a movement to transfer more recycling costs onto the mostly multinational companies that sell packaged consumer goods.

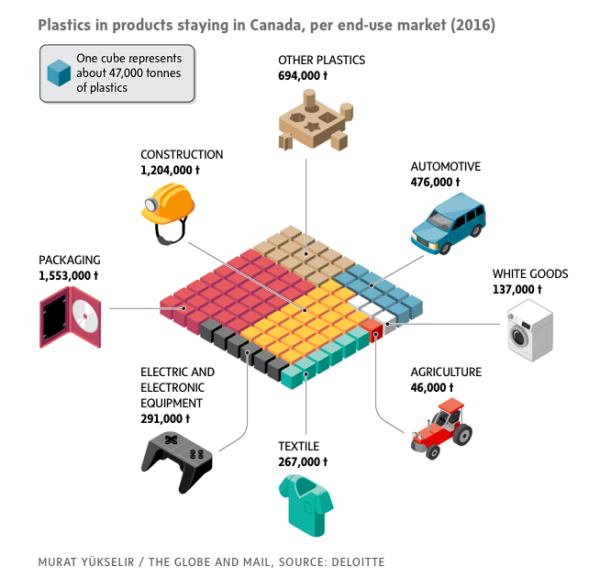

A recent study by Deloitte for Environment and Climate Change Canada shows there is much room for improvement: Only 9 per cent of the 3.2 million tonnes of plastic waste generated each year in Canada is recycled. As much as 2.8-million tonnes – the weight of 24 CN Towers – ends up in Canadian landfills.

This is a “come-to-Jesus moment,” says Jo-Anne St. Godard, executive director of the Recycling Council of Ontario. “We’re going to have to shine a light on those materials that we’ve been sort of hoping would get recycled but, really, at the end of the day, aren’t.”

Ever since Canada’s first curbside program launched in Kitchener, Ont., in 1981, spreading the new gospel of recycling hinged in large measure on making the process convenient. And so, over time, more stuff got the green light to go into the same blue bin, yielding a jumble of waste called “single-stream.” Participation rates soared. But so did contamination.

It was a side effect that mattered less and less as China opened its doors to the world’s recyclables. Although a small Canadian recycling sector emerged, exports to China surged, from Canada and elsewhere. In turn, ships returned from China laden with the consumer goods by which the country was also making its name, many of those cocooned in layers of new packaging.

“All mixed paper – all of it – went to China,” says Al Metauro, executive vice-president at Ontario-based Cascades Recovery, which processes and markets materials on behalf of major Canadian cities.

And so did a lot of plastic. In 2016, around half of all plastic waste intended for recycling was traded internationally, according to a 2018 study published in the journal Science Advances. China and Hong Kong alone imported US$81-billion worth of scrap plastic between 1988 and 2016, the authors said.