National Geographic tells the story of how plastic wrap originated and provides alternatives for the thin, flimsy plastic that is very difficult to recycle.

The slick, transparent film we now know as plastic wrap was originally a mistake of chemistry, a residue clinging stubbornly to the bottom of a beaker in a 1940s laboratory. The military originally used it to line boots and planes. Today, consumers around the world, and the grocery stores they shop in, have more than a hundred brands of the super water-resistant substance to choose from.

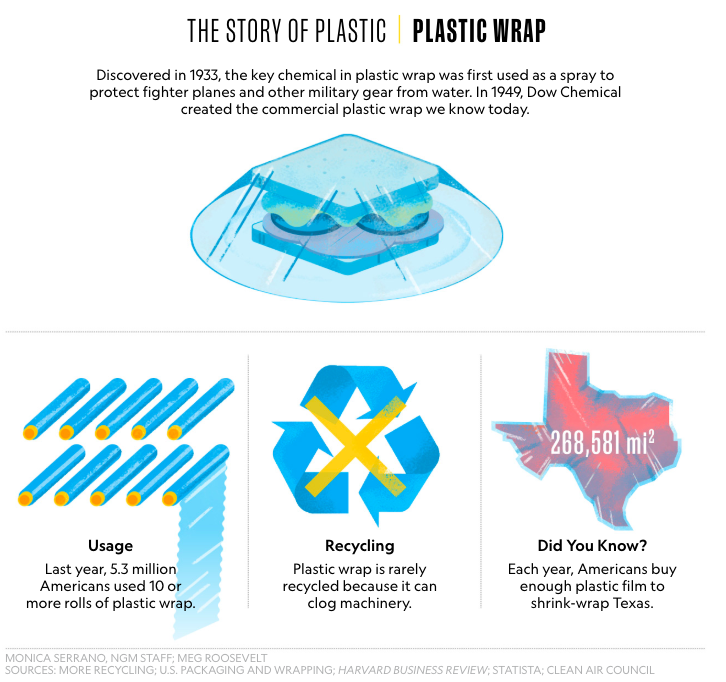

Plastic wrap is popular in the United States. One industry research group found that, in the past six months, nearly 80 million Americans had used at least one roll of plastic wrap, but more than five million Americans had gone through more than 10 million boxes. Commercial uses in supermarkets and shipping account for the additional three million tons of plastic wrap companies expect to make in 2019.

Though the portable, cheap wrap keeps leftovers fresh for longer, there are several catches: Plastic wrap contributes to the larger plastic pollution crisis, it’s difficult to recycle, and it’s made from potentially harmful chemicals, especially as they break down in the environment.

“If you look back to the 1950s when we didn’t have as effective food storage like we do now, you can see why it was so popular,” says Leah Bendell , a marine ecotoxicologist from Simon Fraser University.

“We didn’t have plastic 70 years ago, and then in the post-war boom, you had chemists who were going to provide us with this brave new world. Pesticides, herbicides, and plastics were a big part of that,” she says.

Slick and green

When Ralph Wiley discovered polyvinylidene chloride (PVDC) while working in the physicals lab at Dow Chemical in Midland, Michigan, he nicknamed it eonite after a fictional, indestructible material in the comic strip “Little Orphan Annie.”

His task had been to create a new product out of hydrocarbon and chlorine, two by-products of manufacturing the dry-cleaning agent perchloroethylene.

The newfound chemical was so water-resistant that it couldn’t be washed clean from its distillation flask. PVDC molecules bind together so tightly, they’re nearly impenetrable by oxygen and water molecules. Those properties made the material attractive in war efforts and in American kitchens as Saran Wrap.

By the 1960s, the Australian company GLAD had created its own—though less clingy—version of plastic wrap from polyethylene. Saran Wrap too is now made from polyethylene after consumers grew concerned about the health impacts of wrapping their food in a plastic made with chloride.

Today, consumers around the world have plastic wrap brands at their disposal made of PVDC, PVC, and polyethylene.

Plastic infiltrates the environment

Thin, flimsy, plastic-like bags are difficult to recycle; without specialized equipment they clog machines. And even when plastic wrap is recycled, it’s costlier than using virgin materials. When it ends up in landfills or incinerators, both PVC and PVDC can release a highly toxic chemical called dioxin, says the World Health Organization.

In marine environments, plastic wrap contributes to a larger plastic pollution crisis, but unlike other plastics, scientists are finding that PVC and PVDC do great jobs of picking up bacteria and metals. Those contaminated pieces of microplastic then harm the fish that mistake them for food.

While environmental activists tend to advocate for ditching the product altogether, manufacturers point the finger at outdated infrastructure.

Scott Defife, the vice president of government affairs at the Plastics Industry Association, says plastic films could be easily recycled if our infrastructure for collecting waste wasn’t “lacking.”

“We want the federal government to make investments,” he says. “They should think of it as a critical public utility like roads and bridges.”

The Plastics Industry Association touts plastic wrap as an effective way to reduce food waste by keeping food fresh.

Concerns about safety

PVC and PVDC differ by the slightly different chloride compositions in each molecule. Saran Wrap includes some vinyl chloride, often 13 percent, and both typically have toxic additives, said Bendell. The Food and Drug Administration regulates both, permitting less than a fraction of one percent of PVC and PVDC food wrap from migrating into food. At that exposure level, it’s highly unlikely someone could be poisoned by their plastic wrap.

“If you have a dinner plate made out of PVC, is that posing a risk? Probably not,” says Rolf Halden, an environmental scientist at Arizona State University’s Biodesign Institute. “But if we surround ourselves with PVC and phthalates, they can leach or ooze out of the products. That creates an unwanted exposure.”

In order to make plastics softer, more flexible, and more transparent, they are often mixed with plasticizers, particularly for food packaging, says Ramani Narayan, a chemical engineer at Michigan State University. One common class of plasticizers is a group of molecules called phthalates—a category that contains carcinogens—although PVC plastic wrap doesn’t contain them anymore. It does contain a plasticizer called DEHA, or diethylhexyl adipate, but its effects on human health are unclear.

Three things you can do to be part of the solution:

- Switch from plastic wrap to a reuseable wax wrap.

- Store leftovers in glass containers.

- Cover foods with aluminum foil instead of plastic wrap.

Stretch-Tite makes plastic wrap that contains PVC. In an email, they noted that their product is free of cancer-causing chemicals like BPA and phthalates, and they claim that safety concerns over plastic wrap aren’t based in sound science.

Says Halden: “Unlike infectious pathogens, the effects of toxic chemical exposures may take decades to manifest.” And an increase in cancer rates, for example, would be challenging to tie directly to chemicals in plastic wrap.

The search for alternatives

Wax paper was frequently used in the decades before plastic wrap was stocked on supermarket shelves, and it’s a reusable form of wax paper that’s now offering an alternative to throwaway plastics.

Bee’s Wrap is made by coating bee’s wax, jojoba oil, and tree resin onto a thin strip of cotton. Warmth from your hands loosens the bonds, making it more pliable and sticky.

Co-owner of a start-up called Etee, Steve Reble says he was inspired by the ancient Egyptian wraps on mummies when he created his own version of a reusable food wrap by coating a thin strip of cotton in a waxy barrier.